- Home

- Joseph Andras

Tomorrow They Won't Dare to Murder Us Page 2

Tomorrow They Won't Dare to Murder Us Read online

Page 2

We’re going to shove it up your ass if you don’t talk, did you hear, are you listening? Fernand would have never believed that this was it, torture, the infamous question. The question which requires only one answer, the same, always the same: hand over your brothers. That it could be so excruciating. No, not the right word. Our alphabet is too decorous. Horror can’t but give up before its twenty-six little characters. He feels the barrel of a handgun against his stomach. Pistol or revolver? It pokes in half an inch or so beside the navel. I’m going to blow a hole in there if you don’t talk. Do you understand, or do I have to say it in Arabic?

Jean has urged Jacqueline and Djilali to go back home. It’s more sensible, best not be in the same place for too long. Night dilutes the city in soot, in coal; under a sated sun, the muezzin calls the faithful to prayer, on rue de Compiègne, Jean lights a cigarette and drives straight ahead, arriving at the Chasseriau ramp, where boys are sitting on donkeys, laughing and laughing, Chasseriau … who was he, again? , Jean glimpses a police station on his right, a CRS police van parked not too far away. Empty. After all, why not? The bomb is ready, set to go off at 7:30, all he needs to do is … He brakes abruptly, picks up the package under his seat and gets out. Behind him, cars are honking. He runs over to the van, crazy idea really, lowers the back door handle, it’s open, drivers are shouting behind him, he gets in, slides the package under one of the benches and quickly returns to his car.

Hélène has finally consented to let them in, not doubting that they might indeed “smash the door in.” She rubs her eyes again and explains that she was asleep. They search every room in the house—bathroom included—and inspect every drawer, open every wardrobe, pull out the bedlinen, leave clothes strewn on the floor, return nothing to its proper place. One fat officer, more zealous than the rest, meticulously checks the food containers. Hélène, annoyed, points out that he should be more careful and respectful of others’ property; the fat officer does not look up, he keeps at it, nose deep in rice and rye flour. One of his colleagues entreats him to listen to Madame Iveton and conduct the search with more restraint. A letter, guys, look, I found something! A cop proudly displays mail from Hélène’s father, written in Polish. Both of them are originally Polish, in fact, and this is family correspondence, nothing more: Joseph asking after his little Ksiazek, as she was known before she came to France. And to think the police take these sentences for a coded message; Hélène smiles to herself.

Fernand’s body is almost entirely burned. Every part of it, every bit, every inch of white flesh has been electrocuted. He is made to lie on a bench, still naked, head hanging backwards over nothing. One of the police officers puts a wet blanket over his body, while two others tie him securely to the bench. Your second bomb’s going to blow in an hour. If you don’t talk before that we’re going to do you right here—you’ll never see anyone again, you hear, Iveton? Fernand can finally have a look around the room: they just took his blindfold off. He has trouble opening his eyes. The pain is too sharp. His heart twitches, needles, barbs; he spasms again. Colleagues of ours are at your place right now, haven’t you heard? With your little Hélène, and from what they just said over the phone she’s quite a looker, your wife … you wouldn’t want her to get hurt, would you? So you’re going to tell us where the bomb is, okay? An officer puts a piece of cloth over his face and the water starts to pour. The rag sticks, he can no longer breathe, he swallows water as best as he can to try to get some air but it’s no good he’s suffocating his stomach swells and water flows flows flows.

Seven o’clock in the evening. The unknown contact, Yahia, the one Fernand was supposed to meet after work, is waiting by the factory. He has borrowed a car for the occasion, to cover his tracks in the event of an investigation. Never wait more than five minutes: an order no comrade should ever ignore. Punctuality is paramount for militants, they say, it is our backbone and our armor, any delay is conducive to debacle. 7:06. Yahia stays in the car and decides that, this time around, he’d better wait for Fernand. Who knows, a talkative colleague might be holding him up by the machines. 7:11. He gets out, glances around, takes his pack of Gauloises Caporal and lights a cigarette (another one the FLN won’t have: Yahia chuckles at the thought of the Front’s strictness—bordering on madness—regarding tobacco).

Five more minutes and you’re done, dead, bye-bye! Water drips from his nose, he can’t breathe. His temples throb so much he imagines them exploding any moment now. An officer, sitting on him, punches him in the stomach. Water squirts out of his mouth. Stop, stop, enough, Fernand can only mumble. The officer straightens up. Another, next to the faucet, turns the water off. Alright, I know where the bomb is … Fernand knows nothing of the sort, of course, since Jacqueline took it with her. Rue Boench, a workshop … I gave it to a woman, a blonde, yes, that’s right, blonde … She had a gray skirt and drove a 2CV … I don’t know her, my bag was too small to fit both in, she took the other one and left … A blonde, that’s all I know … The chief requests the order sent, no time to waste, to all available patrols: scour Algiers with the present description. The cloth blocking his mouth and nose is removed. You see, Iveton, it wasn’t that hard. D’you really think we enjoy doing this kind of thing? We just don’t want there to be innocent victims because of your shit, that’s all. That’s our job, Iveton, I would even say our mission—to protect the people. You see: soon as you talk, we leave you alone … All of his torturers sound the same, Fernand can’t distinguish between their voices anymore: similar timbre, just a lot of noise, goddamn hertz. What Fernand does not know is that the general secretary of police in Algiers, Paul Teitgen, made it explicitly clear, two hours ago, that he forbade anyone from touching the suspect. Teitgen had been deported and tortured by the Germans during the war. He could not understand why the police, his police, that of the France for which he’d fought, the France of the Republic, Voltaire, Hugo, Clemenceau, the France of human rights, of Human Rights (he was never sure when to capitalize), this France, la France, would use torture as well. No one here had taken any notice: Teitgen was a gentle soul, a pencil pusher offloaded from the metropolis just three months ago. He had brought his dainty ways along in his little suitcase, you should’ve seen, duty, probity, righteousness, ethics even—ethics my ass, he knows nothing about this place, nothing at all, do what you have to do with Iveton and I’ll cover for you, or so the chief had decided without hesitation. You can’t fight a war with principles and boy-scout sermons.

Yahia crushes the butt of his cigarette under his shoe and goes back to his vehicle. Twenty minutes late: it can only mean the worst. He starts the car and runs into an army blockade, about a hundred yards away. Military trucks have closed off the surrounding streets. Papers, please. Yahia is sure of it now: something’s happened to Fernand. A second soldier approaches to tell his colleague to let him through, he’s not a blonde and this isn’t a 2CV, we’re not about to start stopping every damn car. Yahia thanks them in a friendly voice (without overdoing it, either) and hurries to Hachelaf’s place—if Fernand is tortured, he might end up talking. They have to warn every contact he is liable to give up.

Hélène is in the back of one of the three Tractions Avant. They take her to the police station on rue Carnot, sit her down on a chair in front of a gleaming wooden desk. The chief comes in and asks, without explanation, what color her skirt is. Hélène, who does not understand the point of the question, replies that her skirt is gray. Gray, like the one our suspect is supposed to be wearing! the chief exclaims.

Fernand is still on the bench, tied up, slowly catching his breath. He knows he will be tortured again when they return from the workshop, but he nonetheless takes advantage of the small respite, this unlikely lull in the proceedings. His head is pounding. Torn up. Eyes half closed, he gazes, slack-mouthed, at the ceiling. His genitals hurt especially—so much so that he wonders in what state he’ll find his balls when all of this is over. The door opens, he turns his head slightly to the right, hears them yelling,

the apes coming in, tricolor-clad Gestapo. A brutal kick twists his lips. You took us for suckers, didn’t you, you piece of shit, there was nothing in the workshop … we’re going to fuck you up good.

Hélène has just been apprised of the situation: her husband has been arrested for planting a bomb, which was immediately defused: the police were called to his factory in Hamma, and found papers on him indicating that another explosive device was supposed to go off—any minute now, in fact. She had no idea, she answers, truthfully. Of course, she is not unaware of Fernand’s political views, of his activities in circles of which she knows neither the ins nor the outs, of course she suspects that he could, one day, radicalize further and seek to translate words into action, but she never imagined him capable—is that even the proper term?—of committing, or even wanting to commit, a deadly attack. All she says aloud, however, is that she was entirely ignorant of Fernand’s militancy; she loves the man himself and does not care whether his heart beats left or right, as long as it beats by her side. Do you take us for fools, Madame Iveton? She smiles. Her calm is not just a mask, a display of bravado, a protective swagger. Not at all; Hélène has, throughout her life, always known how to maintain the elegance and bearing people expect of her in any situation. You should talk, Madame Iveton, fact is we have a lot of information on your husband, some of which, I’m sorry to say, might hurt you: he’s been cheating on you for a while now, with a certain Madame Peschard. Hélène does not believe a word of it. Their speech is heavy and ill-sounding, clumsy, the flimflam of officials and servicemen. She smiles again, before remarking: I hear adultery is fashionable now, I shouldn’t be surprised if you, too, chief, were every inch a cuckold.

Fernand has fainted. He had the sensation, right before passing out, that he was about to drown, his lungs filling up completely. An officer slaps his cheeks over and over to bring him round. He’s not going to give out on us like that, is he? Teitgen wouldn’t be happy. Mr. Ethics. That office clerk from Paris, with the soft heart, all lovey-dovey. They laugh.

Yahia does not find Hachelaf at home, only his wife, who is not aware of anything. He goes to Hachelaf’s garage and, after about half an hour, sees him coming up on his Lambretta. He motions for him to stop and explains the situation in a few words. Hachelaf has not had any news from the group, but he was surprised, listening to the radio, not to hear of an explosion at the factory. Yahia offers to hide him for a few days at his European friends’, the Duvallets, they’re good people, you’ll see, and it’s only until we find out exactly what’s happened to Fernand. He accepts.

Hélène is taken to a cell. Rounded-up prostitutes a few meters away. The water has been cut off.

Fernand comes to. Everything is dim, cops’ faces are leaning over his, and his nasal cavity is a violent, searing pain. He wants to vomit. An officer asks the others to stand back and sits on a stool, the very same on which the generator stood only a few hours earlier. He speaks to Fernand in a calm voice. Friendly, even. He has shown courage—it’ll be to his credit—but it’s useless to keep this up, come clean once and for all and we’ll leave you alone, you’ll go rest in your cell, no one will hurt you, you have my word. Time’s up, you see, we’ve heard no report of an explosion, your blonde in the 2CV must’ve found a way to defuse it … It’s all over, you can tell us the rest, we just want to know who you work with: names, Europeans, Muslims, and don’t tell me you don’t know anyone. Honestly, I don’t know anyone, Fernand affirms it … Get back to it, guys.

Prostitutes of every size and shape, varicolored, fullcheeked, plump, bamboo-thin in fishnets, wrinkled or otherwise marked by the smoothness of a desecrated youth. Hélène is sitting at the back of the cell; the cold seeps under her dark green coat. Fernand always said that he condemned blind violence on both moral and political grounds. This arbitrary shredding of bodies, chalking up victims at random—it’s a throw of the dice, a sordid lottery on any street, café, bus. Though on the side of the Algerian independentists, he did not approve of their every method: barbarity cannot be beaten by emulation, blood is no answer to blood. Hélène remembers other attacks, that of the Milk Bar and others, and how Fernand worried, telling her over coffee (black, no sugar), his forehead more wrinkled than usual, that it wasn’t right to place bombs just anywhere, not right, not at all, to place them among little girls and their mothers, grandmothers and humble Europeans, people without a dime. It could only lead to deadlock. An officer stops in front of the cell and taunts: Iveton, tête de con! Hélène stands up. Come say that to my face if you’re a man, open up and come say it. The prostitutes clap and let out a few bravos. A baton runs noisily along the bars, demanding immediate silence. Fernand would never have placed a bomb in the factory knowing it would kill workers, of that she is certain. He probably expected the building to be empty. A symbol. Sabotage, in sum.

Let him be, that’s enough, or we’ll lose him. Fernand is no longer answerable for anything. An unrelenting throbbing inside. Organs like so many wounds. He begs for the water and the blows to stop. It’s late, his comrades must know he’s been arrested, they’ve had time to hide. Alright, wait, alright … I know two people, no more, I swear, Hachelaf and Fabien, a worker, Italian family, he’s young, in his twenties … Fernand has no idea who he is talking to and, in truth, knows nothing but the fact that when he talks the torture stops. I don’t know anyone else, you have everything. An officer writes the names down in a leather-bound notebook. That’ll do for tonight, take him to his cell. He is unable to move by himself: they carry him, naked, to the cell, and toss his clothes nearby. Rats scurry in the corners. Sleep prevails over pain: he collapses a few minutes later.

The River Marne sticks out a green tongue to the sky’s peaceful blue.

Clumps of trees unsettle an otherwise rigid horizon.

Fernand is in a short-sleeved shirt and his thin mustache has been freshly trimmed. Up above, the sun oscillates between two wrinkled, if ageless, clouds; down below the grass is speckled with poppies. There are hardly a thousand souls in this village of Annet. Fernand waves at an old fisherman and at someone who must be the fisherman’s grandson. The hospital doctor was right: he can feel that, too, he’s getting better. The air of the mother country is not without merit. Might he even, before too long, step onto a pitch again and play the soccer he loves so much? Be patient, be patient, said the aforementioned doctor, in a voice calmer than the Marne.

Fernand sings, something he goes in for whenever the walk or the mood demands it … The trees in the night lean in to listen to this sweet song of love … A tango. Carmen. The women of Clos-Salembier, his childhood neighborhood, always maintained that he had a nice wee voice, with a certain something in its timbre, a catchy roll, and that he should’ve tried his luck (they’d go on and on about it) in the cabarets or music-halls of Algiers. The birds say it again so tenderly …

It must also be acknowledged that the presence of pretty Hélène, whose first name is as lovely to the ear as her namesake, has played a part in his convalescence. She is from Poland, he gathers, overhearing a conversation she had with customers some two weeks ago. Her hair is thick and a distinctive shade of blonde, not unlike hay (slightly dark, matted and rough). Her eyebrows are thin, a pen line at the most; her chin is dimpled and she has prominent cheekbones, the likes of which he has never seen: two promontories above large cheeks. Every evening, or almost (a painful almost, since it marks her absence), Hélène helps her friend Clara, who runs the family pension where Fernand is staying, the Café Bleu. She makes appetizers and desserts. During the day, she works at a tannery not far from there, in Lagny—a village, she told him four days ago, that was virtually destroyed during the Great War. The first time Fernand saw her, she was serving wine to a couple seated a few meters away from him. Hélène appeared edgewise, her perfect profile projected on the wall behind her, that shadow slightly swollen, in the middle, by her nose. He noticed her smile, and that cheek—he saw only one at first, obviously—a Mongol’s cheek (Fernand has n

ever met any Mongols, but that at least is the image in his mind). And then those eyes: their far-flung blue, journey and meridians for the North African kid he is. Two little tablets, pointed and cold, colored the kind of wolf-dog blue which rummages around your heart, never asking for permission or wiping its feet on the doormat—for this blue would not fail to make a doormat out of you, one day, if it could ever come to blame or love you. He had used indecision as an excuse, at a meal last week (the choice was caramel-cider tartlet or strawberry crème brûlée), to incite their first exchange. She was partial to caramel and asked him where his accent was from: from Algeria, ma’am, it’s my first time in France, well, yes, they say Algeria’s in France, sure, but still it’s not the same, you have to admit that it’s …

She is here tonight.

Fernand sits down and orders the set meal. Her eyes are little frosted pearls, she smiles and goes off with his order, explicit creases at the back of her skirt, ankles as slender as her wrists … Hélène was born in Dolany, a village somewhere in the middle of Poland. Her parents named her Ksiazek at birth, and the family, the three of them and her brother, migrated to France when she was eight months old. For work. They were agricultural laborers. Her father is called Joseph—like the Judean carpenter or the Little Father of the Peoples, the choice is yours—and her mother Sophie. He plays violin and she comes from a wealthy family. She let her class down to escape with the man she chose to love … too few hearts are ready to break ranks. They settled in Annet, with chickens, rabbits, four pigs and a few pigeons.

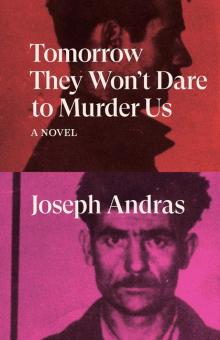

Tomorrow They Won't Dare to Murder Us

Tomorrow They Won't Dare to Murder Us